By Betty Miller Conway

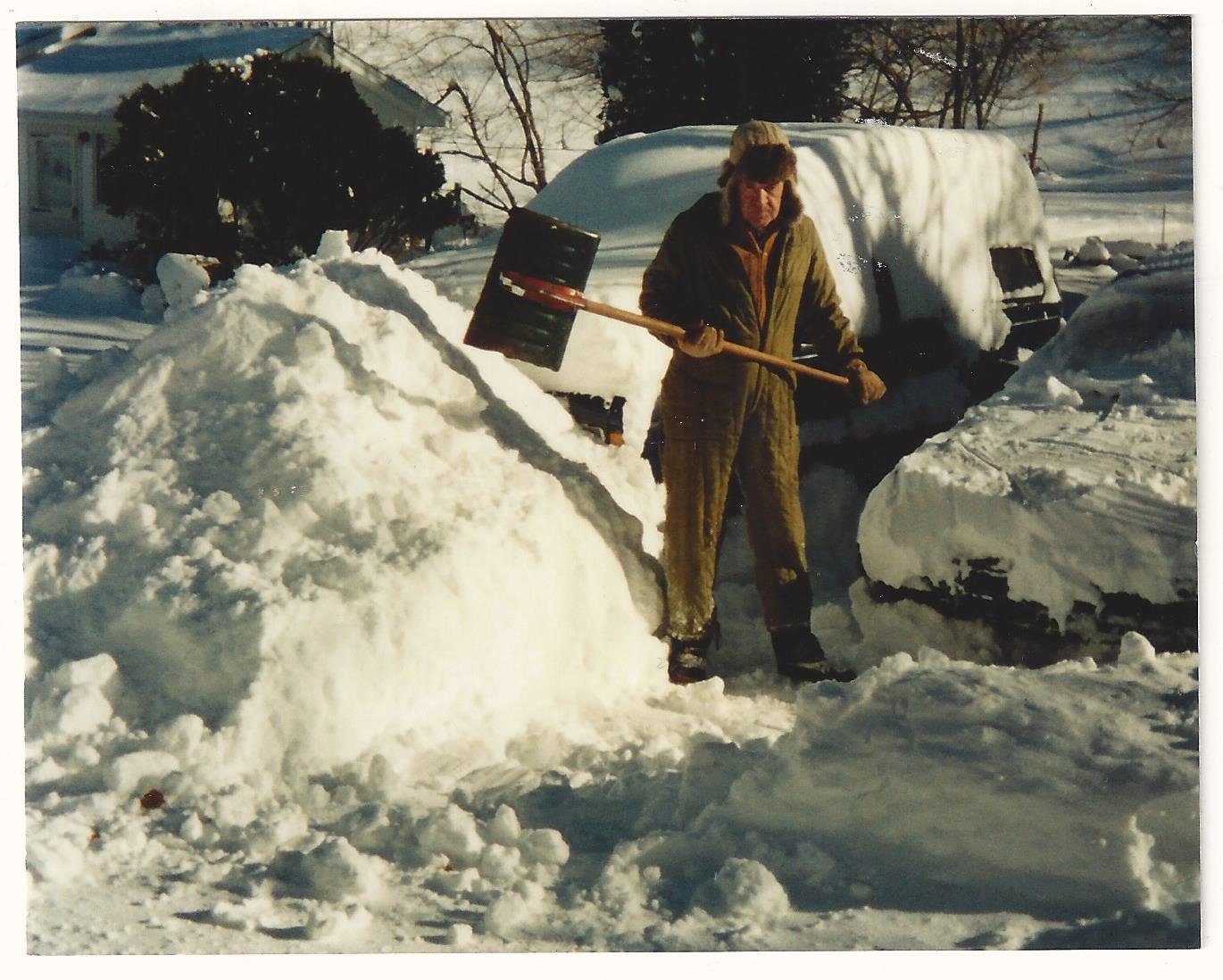

The wind is howling, and the snow is whirling around my windows trying to get in. The forecast is ominous: a foot or more of snow and ice for the North Carolina mountains! But I am prepared. I have filled all the bathtubs with water, bought enough provisions for a winter in Alaska, charged all the phones, and replaced the batteries in our flashlights. I made sure that Walton brought in enough firewood to last at least a month and that he put the scraping blade on the tractor. The animals are safely in the barn with plenty of hay, and our matching pair of insulated Carrhart coveralls is hanging in the mudroom, ready for wear. There will be no eggs today.

It's a Miller B storm. That’s a type of complicated Nor’easter storm that has the potential to bring heavy snow—or worse, a combination of sleet and freezing rain—to the Appalachians. Since my family name was Miller, it was a standing joke in our family that a Miller B storm was messy and difficult, not unlike our own family dynamics during my turbulent teenage years. I’m not sure any of us totally understood the nuances of a Miller B forecast, but we knew enough to prepare for trouble! I remember my dad calling me once while I was out of town, warning me to come home before the winter weather started. “It’s a Miller B Storm,” he announced somberly. I knew exactly what he was talking about and dared not tarry on my way home.

It’s kind of strange and somewhat paradoxical that I know or care anything at all about meteorology. I am not scientifically oriented in any other way. When I was in college, I dreaded chemistry class almost as much as going to the dentist. Although I am interested in the idea of science—passionate about nature, animals, and the workings of the universe—I’ve never had much patience in the methodology or classification of science. When Walton and I go birding, for example, he alternates between his binoculars and the bird guide identifying and classifying each bird we see. I, on the other hand, am more apt to daydream under a tree listening to the bird song and the rustle of the wind in the treetops. It does not matter much to me what species of bird is singing. It is all lovely to me. And when Dr. Lang comes out to treat our animals, I’m not so worried about the science behind his diagnosis as I am the practical ramifications of his findings: What caused this problem? How do I fix it? At one point I aspired to be a veterinarian but quickly realized that I would never make it through the methodology of the science.

Nevertheless, I love learning about weather. I am fascinated with the vocabulary of weather. It seems to me that weather terms like deep trough, warm nose, Polar Front, and moisture starved belong in a poem instead of my local forecast discussion. I like to watch the radar and see the storms swirling though the automated maps. I embrace the statistics and probabilities associated with weather forecasts. My favorite is the forecast that predicts “clear skies, calm winds, with a high of 70.” (That’s perfect horseback riding weather). That forecast happens far less often than I would like. Usually there is at least some probability of precipitation in our mountain area. In the summer, I’ve learned to be satisfied with a “30% chance of scattered thunderstorms in the afternoon.” My least favorite forecast in the winter is the one that mentions a “100% chance of freezing rain and sleet.”

My fascination with weather has deep roots. As a farmer, my dad could always tell you the latest weather news. He could recite the forecast in his sleep! He was the epitome of “weather prepared,” often putting chains on his old station wagon the night before a storm so that he could shovel out and make it into work the next morning. It was against the Miller creed to ever miss work because of the weather. He and my Uncle Lloyd collaborated on the winter weather, discussed if they needed to put livestock in the barn, and made bets on how high the snowplow berm was going to be.

As survivors of the 1940 flood, they were especially mindful of heavy rain forecasts, since part of our farm was a flood plain. On the most threatening of nights, my dad insisted that we evacuate to my Aunt Margaret’s house which was the house that he grew up in. Built in 1899, it had withstood many a flood. My dad remembered standing on the back porch and watching a house float down the flooded pasture beyond. It had chickens on the front porch! Since he was a young boy, that sight must have scarred him for life because he never took a chance that his family would be stranded on the wrong side of that creek. As a child, I loved evacuating to Aunt Margaret’s and listening to the rain thunder on the old tin roof. I was secretly excited when the forecast was for a 100% chance of heavy rain. But of course, I never told my Uncle Lloyd and Daddy that.

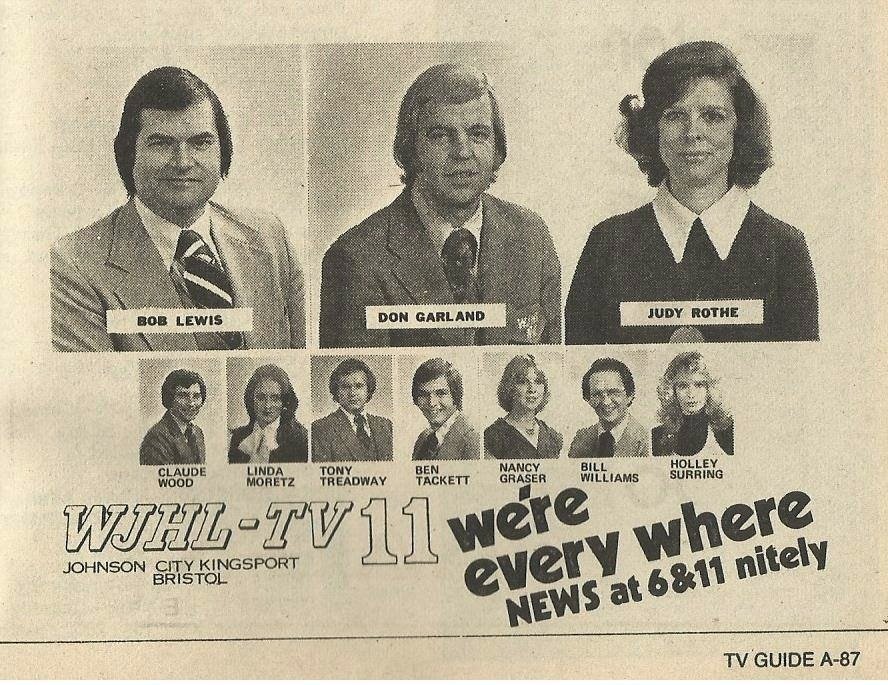

My dad and uncle relied on Judy Rothe for weather guidance. When I was a teenager, Judy Rothe worked as the lead meteorologist for WJHL TV in Johnson City, Tennessee. That must have been groundbreaking at the time since even now, women are under-represented in the meteorology field. Having a woman tell the weather certainly caused quite a stir in my household! It was the mid-seventies, but she wore pointed collars, a modest suit, and had her hair flipped up in a pageboy cut. There was no glitzy embellishment and no drama in the discussion like there often is today. Certainly, she didn’t need menacing music to accompany the forecast; instead, Judy Rothe just told it like it was.

Daddy and Uncle Lloyd loved her! My mother and Aunt Josephine, well, not so much. They complained that Judy Rothe and her weather preview interrupted their carefully prepared hot suppers. Even when the upcoming weather wasn’t dicey, Daddy and Uncle Lloyd had a hard time sitting though their meals if Judy Rothe was on the television. Once, when Daddy yet again jumped up from the table to watch the forecast with a hamburger in one hand and his coffee in the other, my poor mom exclaimed, “He thinks more of Jody Rothe than he does of me!” My little sister, Ann, and I giggled into our napkins because we understood why he did it. We loved Judy Rothe, too.

We all called her the weather woman. Or referred to her by her full name, Judy Rothe. Never by just her first name which seemed disrespectful. She was accurate, and reliable, qualities that my family admired in people. Toward the end of her tenure she was pregnant, and we all found that to be both interesting and unusual. (Except for my elderly Aunt Margaret who maintained that no woman had any business being on television pregnant)

We were all disappointed when Jody Rothe left the local TV station. We were forced to rely on other, less endearing meterologists. By then I was in college at nearby Appalachian State University, but I still paid attention to the weather and made sure I had chains on my car if there was a chance that snowy roads could hinder my chances of getting to class—or me making it to my part time job at the Hallmark shop at the local mall. I knew how to put chains on, but I hated how hard the clasps were to close when my girlish hands were cold and stiff.

But I need not have worried. If the weather deteriorated while I was in class, my dad would find my car in the parking lot during his lunch break from the post office and put my chains on for me. The students who lived on campus would be shouting with glee and having snowball fights as I got into my little Ford and headed toward work accompanied by the steady clink and chime of tire chains. Many years later, I would remember those chimes when I became a teacher at that very same university. By then, my dad was not there to put chains on for me. I had a 4WD Subaru station wagon which usually didn’t need chains, thank goodness. I made certain I never missed one day of work due to the weather. It was against the Miller creed.

One wild winter day at work, I received an unexpected invitation to be a weather spotter and volunteer for CoCoRaHS, a community-based weather project based out of Colorado that aimed to collect backyard weather data from all over the country. Well, really, it wasn’t a personal invitation—just a blanket email to all the faculty at the university. But you would have thought I had a letter from the president of the United States! Eager to do something besides look at first-year composition papers, I immediately signed up, did the training, and was happy to eventually get an official, heavy-duty rain gauge in the mail. This was before the era of home weather stations and electronic gauges. My job was simply to erect the gauge in an acceptable spot, check it every morning, and report the volume.

And I did so faithfully. I viewed it as a mission. Walton watched in amazement as I trudged by him every morning, even before the requisite morning coffee, to the far end of the yard and measured the precipitation with uncharacteristic precision. In the winter I took a yardstick to measure the snow on the ground, too. Sometimes I even melted the snow in the gauge to see how much water the snow was comprised of. Then I faithfully reported all information and weather notes to the CoCoRaHS website. Once, on an especially hectic morning, I forgot to check the rain gauge before work. In a panic I called Walton from my office and begged him to measure for me so I could report on time. He was enjoying a leisurely breakfast. He looked out the window at the pouring rain and very pleasantly told me that CoCoRaHS could do without my report for one day! I guess he was right. My only regret about the first year was that there was a drought over the summer giving very little to report. Nevertheless, I bought CoCoRaHS rain gauges for family and friends that Christmas. At least my sister appreciated hers.

One benefit to being part of this weather community was that I got weekly emails from the head of that department, Nolan Doesken. Those emails were a treasure because not only did they provide all kinds of weather information that weather nerds like me enjoyed; they also included stories about Nolan’s Great Pyrenees dogs, his family farm, and his chickens. I think all of us volunteers mourned when Rose, his oldest dog, succumbed to cancer. I especially appreciated his anecdotes about the trials of feeding animals in the snow. I don’t actively participate in weather reporting anymore since so many people have fancy electronic weather stations in their backyards and businesses that do the same job. But I still read Nolan’s personable weather emails and marvel at how he can turn the most technical weather data into a story.

That’s true of the best meteorologists I know. Ray Russell, our local online weatherman, is a friendly kind of guy who flashes you a big grin and waves when you see him at the grocery store. Although he does not engage his readers with a lot of technical jargon, I know to pay attention when he warns there may be “mischief” ahead and to breathe a sigh of relief when he announces that there “is not much action” in the upcoming forecast.

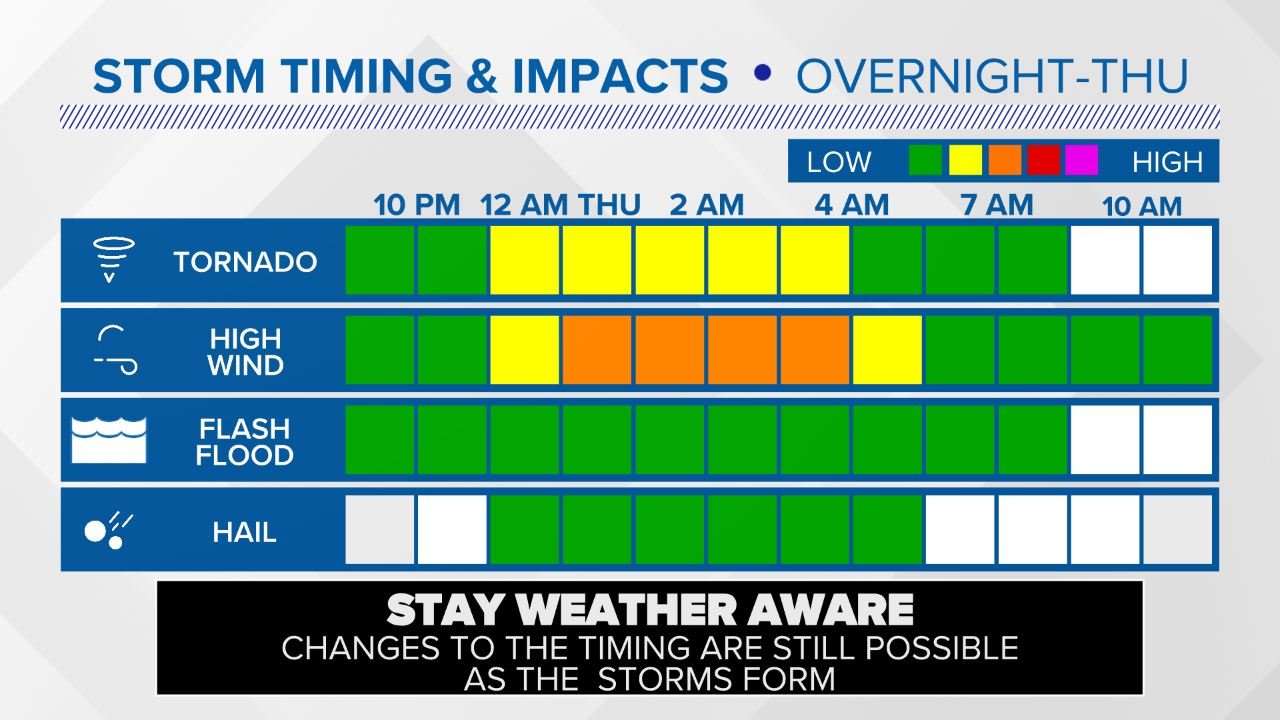

Similarly, Brad Panovich, whom I follow on Facebook and occasionally see on the nightly weather on TV, is earnest and dedicated. He keeps the weather real by sharing family anecdotes with us. His live Facebook updates from home—sometimes in the middle of the night! —ensure that we are educated and informed. Really, I’m not sure that the man ever sleeps! His passion for the weather is unfailing. Not surprisingly, Brad maintains that weather is his “favorite topic of conversation” (mine too!), and he always encourages his listeners to be “weather aware,” which pretty much sums up my entire existence.

New technologies and the internet certainly make it easier than ever to keep up with the weather. I check the weather forecast every morning, not only for our area but also for the cities that my daughters live in. I’ll bet I’m one of the few people in North Carolina who can tell you with precision that the probability of snow in Taos, New Mexico, today is 20%, that Raleigh, North Carolina, is due to get two to three inches of snow, and that Washington DC will be cold with gradual clearing. Even though my daughters are in their twenties and thirties, I still call them and remind them to bundle up if it is going to be chilly and to stock up on food and water if an ice storm might be on the way. Of course, if I suspect that a Miller B storm might impact their travel plans, that warrants a Zoom meeting!

My daughters do not understand my passion for weather, but they are patient with my constant weather updates. This last year for Christmas, Mary Ellis even purchased me an outside electronic weather station. Ironically, we haven’t gotten it installed yet because of the weather! But when the wind quits blowing long enough for me to stand upright, it’s one of the first things on my “to do” list. Then I’ll be able to monitor the wind speed, temperature, precipitation rate, and other important weather variables on my phone. I will be my own weather woman! Walton worries that this does not bode well for my chores and accounting tasks, but I tell him that these are only trivialities—really, it’s more important to be weather aware.